21CS Guide to Understanding Tariffs

“It must be clearly understood, and we say it in all frankness, that the only way to solve the problems now besetting mankind is to eliminate completely the exploitation of dependent countries by developed capitalist countries.”– Che Guevara, from his speech at the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (March 1964)

Our struggle for socialism is rooted in our specific context in the 21st century United States. To that end, we must understand our local and material conditions and put present disputes into their proper context. Here in the United States, after the better part of a century of deindustrialization and financialization, left-wing organizations have come to largely ignore issues of the productive economy to focus instead on issues of domestic redistribution within their own borders. However, the Trump administration’s recent announcements on tariffs—and their stop-and-go implementation—has brought the issue of production to the forefront. As socialists, we must address the underlying issues of production, imperialism, and international value transfers. This guide seeks to put the current discussion of tariffs into context so that we can better understand—and ultimately change—United States policy towards the rest of the world.

It’s difficult to quantify exactly how much the United States has extracted from other countries over the past few decades. That’s partly because it has used so many different tools to screw over the rest of the world. The United States essentially prints money and then exchanges it for real goods like coffee beans, oil, and lithium. It inflates the prices of what it provides (finance, marketing, etc.) and drives down the salaries of the people working in the physical world. The high salaries on Wall Street and in Silicon Valley and the low wages in the Global South are deeply connected. Estimates put these “value transfers” (i.e., thefts) north of $100 trillion. For our purposes, we’ll just say that it’s a lot.

The Trump administration’s tariff policy is United States capitalism’s latest effort to reassert itself, extract more concessions from weaker international parties, and break the links of cooperation among the countries of the Global South. In particular, this policy is an explicit attack on the People’s Republic of China (PRC). It is our duty as internationalists and anti-imperialists to ensure that this attack fails. This will require a re-orientation of left organizations within the United States and a more explicit break from the policies that have been advanced by Republicans and Democrats alike.

Keeping the focus on relations of production

Relations of production are absolutely fundamental to any kind of socialist analysis or organizing. That’s the whole reason why Karl Marx wrote three heavy volumes of Capital in the first place. He didn’t do it because it was fun, but rather because he saw some of his contemporary leftists bumbling around the issue and wanted to convey a bit more clearly that any society’s method of producing socially necessary things is fundamental to understanding (and changing) that society. He didn’t want his well-meaning allies to trip over themselves making the same mistakes.

Marx was very explicit that focusing on the “mode of production” was essential to understanding, and then transforming, the world. When left-wing groups—even allies—strayed from this point, he was also quick to correct them. For instance, in his Critique of the Gotha Programme from 1875, Marx was very critical of what he viewed as “vulgar socialism” that had lost sight of this point and focused instead on redistribution through social welfare programs. For those interested in hearing it directly from the man himself (emphasis ours):

Any distribution whatever of the means of consumption is only a consequence of the distribution of the conditions of production themselves. The latter distribution, however, is a feature of the mode of production itself. The capitalist mode of production, for example, rests on the fact that the material conditions of production are in the hands of nonworkers in the form of property in capital and land, while the masses are only owners of the personal condition of production, of labor power. If the elements of production are so distributed, then the present-day distribution of the means of consumption results automatically. If the material conditions of production are the co-operative property of the workers themselves, then there likewise results a distribution of the means of consumption different from the present one. Vulgar socialism (and from it in turn a section of the democrats) has taken over from the bourgeois economists the consideration and treatment of distribution as independent of the mode of production and hence the presentation of socialism as turning principally on distribution. After the real relation has long been made clear, why retrogress again?

In short, Marx is asking if these folks even understood why he wrote so many words about the economic details of linen production and whatnot in his three long volumes of Capital. Weren’t they paying attention? Why go backwards, after all that trouble?

In the years after Marx’s death, as the world powers drifted towards imperialism—locating production abroad and redistributing value back home through naked colonialism—various left-wing movements drifted further away from Marx’s lessons. Imperialist competition for spheres of domination, and the strategic imposition of tariffs, led to increasing conflicts between nations. The rise of monopoly capital and imperialist superprofits further led to conflicts within left-wing movements. Even among the loosely organized socialists within the Second International, reformists and national chauvinists sought to maintain their nations’ privileged positions at the expense of the international working class. With the outbreak of World War I, these internal conflicts ultimately led to major splits within the socialist movement and the end of the Second International.

This was a key moment when segments of Western socialists became alienated from the rest of the world and confused in their analysis of capitalism. It’s important that we learn from these lessons and not repeat them. We must understand what is happening and fight against imperialism within our own country.

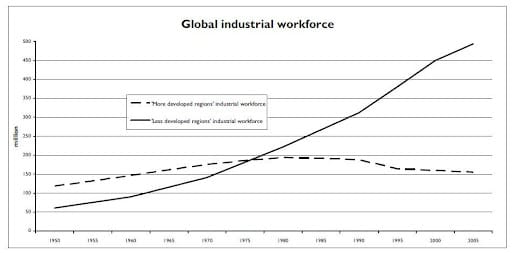

The shifting location of world production

Over the past century, and particularly after the end of World War II, the United States has rapidly deindustrialized, moving toward an economy based on finance capital, imperialist value transfers, and rent-seeking. Instead of manufacturing socially useful things, it has shifted toward Wall Street shenanigans, exploitative loans to the Global South, real estate speculation, and marketing. The United States literally wrote the rules for international finance and trade, first with the 1944 Bretton Woods agreements—creating both the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank—and next with the 1947 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (the precursor to the World Trade Organization established in 1995).

Donald Trump’s claim that the rules of trade and the rest of the global financial system are somehow “unfair” to the United States is obviously an absurd lie. Pretty much everyone in the world—including United States officials—acknowledges this. One of the most obvious benefits that the United States receives relates to the status of the U.S. dollar as the “global reserve currency.” Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, France’s former Minister of Finance, remarked that the dollar’s status as the global reserve currency bestows an “exorbitant privilege” on the United States, paid for by the rest of the world. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York pretty much brags about it in its December 2022 publication “The Dollar’s Imperial Circle.” That’s pretty blunt. Congress is even more explicit, not just admitting that this privilege exists but saying that they want to keep it forever. On June 7, 2023, the U.S. House Financial Services Committee held a hearing entitled “Dollar Dominance: Preserving the U.S. Dollar’s Status as the Global Reserve Currency.”

So what does this “dollar dominance” really mean, in practice? In short, it means that the United States can act like it has a “magic money tree.” The United States can print money when it likes, while the rest of the world can only acquire U.S. dollars by providing goods and services. If they want to conduct major economic transactions (e.g., buying oil from OPEC countries), they’ll need to do so in U.S. dollars. This allows the United States as a whole to acquire the goods and services produced by other countries essentially for free. Although socialists might be excited about the idea of “money for nothing,” it’s important to critique this arrangement because it has tremendous impacts on the international working class.

Deindustrialization and “dollar dominance” have gone hand-in-hand. After all, once the United States hit upon the idea that it could just exchange dollars with other countries for goods and services, it no longer had the same need for its industrial base—with its associated inconveniences such as strikes—in order to accumulate capital. Industrial production thus shifted to the Global South. This is not a recent trend—this type of deindustrialization started long before the “free trade” agreements like NAFTA were signed.

As the United States (and its European allies) went through these transformations, it also tried to keep the rest of the world in its place through deeply unequal arrangements. The Global South would export raw materials and simple manufactured goods (all of it under-valued), whereas the United States and its allies would over-value their own contributions through loans (largely benefitting Wall Street) and marketing (largely benefitting Silicon Valley), among other things.

The unequal relationships are perhaps best illustrated by an example from a book from John Smith (yes, that’s really his name) called Imperialism in the Twenty-First Century. A t-shirt made in Bangladesh and sold in Germany for €4.95 by the Swedish retailer Hennes & Mauritz (“H&M”) goes through a whole cycle that shows these unequal arrangements. H&M pays the Bangladeshi manufacturer €1.35 for each t-shirt (28% of the retail sale price), 40¢ of which covers the cost of 400g of cotton imported from the United States (with an additional 6¢ per shirt in shipping costs). Thus, only €0.95 of the final sale price stays in Bangladesh, to be shared between the factory owner, the workers, the suppliers of inputs/services, and the Bangladeshi government (through taxes). The remaining €3.54 counts towards Germany’s GDP, with €2.05 going to the costs and profits of German retailers, advertisers, etc.—H&M making 60¢ profit per shirt, the German state making 79¢ through its 19% “value-added tax,” and 16¢ covering “other items.”

There is a wealth of Marxist analysis of international imperialist value transfers and the establishment of the current world hierarchy. Socialists must understand this history and interpret current events in light of the role of the U.S. dollar. However, we don’t need to read dense Marxist texts to understand these points, because they are openly acknowledged by the current political class—Democrats and Republicans alike. On March 18, 2025, for example, Vice President J.D. Vance delivered a speech at the Andreessen Horowitz venture capital firm’s American Dynamism Summit, saying (emphasis ours):

The idea of globalization was that rich countries would move further up the value chain, while the poor countries made the simpler things. You would open an iPhone box, and it would say “designed in Cupertino, California.” Now, the implication, of course, is that it would be manufactured in Shenzhen or somewhere else. And, yeah, some people might lose their jobs in manufacturing, but they could learn to design or, to use a very popular phrase, learn to code.

But I think we got it wrong. It turns out that the geographies that do the manufacturing get awfully good at the designing of things. There are network effects, as you all well understand. The firms that design products work with firms that manufacture. They share intellectual property. They share best practices. And they even sometimes share critical employees. Now, we assumed that other nations would always trail us in the value chain, but it turns out that as they got better at the low end of the value chain, they also started catching up on the higher end.

This is essentially Vance admitting what Marxist development theorists have been saying for decades: that the United States and its allies have been pushing for a system that keeps other countries at the lower end of the “value chain.” It’s very similar to the pattern Walter Rodney, the author of How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, identified. However, unlike the Marxist analysis, Vance argues that this kind of international exploitation is a good thing, and that it’s a bad thing when the Global South manages to escape that pattern. He’s saying that his administration is just trying to figure out new ways to meet the same U.S. goal of keeping other countries in a position of exploitation.

This last point is particularly important. As the United States has lost its manufacturing base, and shifted toward these new systems of value transfer instead, it has become all too easy to accept these imperialist relations as “normal.” When the Trump administration says the quiet part out loud, however, the socialist movement has an opportunity to clarify these points and re-orient back into a posture of actual opposition.

The growing counter-example of the People’s Republic of China

Over the past century, China has seen tremendous growth. Even the World Bank had to admit in April 2022 that “China has contributed close to three-quarters of the global reduction in the number of people living in extreme poverty” over the previous decades, “lifting 800 million people out of poverty.” On December 6, 2023, the Financial Times wrote: “Sorry America, China Has a Bigger Economy Than You.” Likewise, on January 17, 2024, the Center for Economic and Policy Research detailed how China became “the world’s sole manufacturing superpower,” whose “production exceeds that of the nine next largest manufacturers combined.” In the process, the country has focused on environmental and social goals, with a March 7, 2024 New York Times article detailing “How China Came to Dominate the World in Solar Energy.” It’s beyond the scope of this guide to get into all the important details, but these are remarkable achievements that chart out a very different path from the one followed by the United States. That this was all done under the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party, with a relentless focus on developing the productive economy and with the assistance of state-controlled financial and industrial development institutions, is an uncomfortable fact for the leadership of the United States.

Rather than attempting to learn from this counter-example, both parties in the United States have committed themselves to crushing it. The shift really went into hyper-drive with the Obama administration’s so-called “pivot to Asia,” and has continued under the first Trump administration, the pathetic Biden administration, and now the second Trump administration. During the first Trump administration, the United States explicitly initiated a new trade war by imposing new tariffs on imports of washing machines and solar panels, steel and aluminum, and various other consumer, intermediate, and capital goods from China throughout 2018 and 2019. Consistent with the statements of J.D. Vance above, the Democrats and Republicans alike have focused on attacking the high-tech sectors of the Chinese economy (i.e., the “higher end” of the value chain), with sanctions and tariffs aimed at the country’s electric car and the smart-phone industries. Even during his lame-duck session in January 2025, President Biden moved forward new rules that “effectively bar nearly all Chinese cars and trucks from the U.S. market, as part of a crackdown on vehicle software and hardware from China.”

The Democratic Party has been particularly terrible on this issue. Rather than de-escalating, the Biden administration chose to “increase Trump-era duties on steel, aluminum and clean energy products from China, including quadrupling tariffs on electric vehicles, while keeping the rest in place.” When Biden ran his failed re-election campaign in 2024, the Democratic Party platform repeatedly attacked Trump from the right on the issue of China, arguing that he wasn’t hawkish enough. The platform warned that Trump would “cede the race for the future to China.” It further warned that the United States was engaged in “intense strategic competition with China” and that we needed to be “leading coalitions of nations who share our values to stand together” against the Chinese communists. It went on:

President Biden recognizes that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is America’s most consequential strategic competitor. The PRC is the only global actor that combines the intention to fundamentally reshape the U.S.-led international order with an increasing military, economic, diplomatic, and technological capacity to do so. President Biden understands the imperative of rising to this challenge while managing the competition between our countries responsibly.

Likewise, in her right-wing Democratic National Committee speech, failed candidate Kamala Harris declared that she wanted to ensure “that America, not China, wins the competition for the 21st century.” The strategy of the Democrats—just like the Republicans—has been to maintain some level of trade with China for the manufacture of “simpler things,” but to absolutely stifle them from “catching up on the higher end.”

The Trump administration’s latest actions need to be understood in this context. Both parties have recognized that the PRC’s economy has been rapidly growing and that China’s intense focus on the productive economy has put it in a better position than the shaky, financialized United States economy. Both parties have committed to destroying it. Socialists cannot quietly accept this status quo as part of some kind of “alliance” with the Democratic Party.

U.S. tariffs: history of economic war

The United States has a long, shameful, and particularly cruel history of using economic policy as a weapon. In an April 6, 1960 memorandum (i.e., shortly after the success of the Cuban revolution in 1959), the Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs stated the policy quite plainly:

Salient considerations respecting the life of the present Government of Cuba are:

1. The majority of Cubans support Castro (the lowest estimate I have seen is 50 percent).

2. There is no effective political opposition.

3. Fidel Castro and other members of the Cuban Government espouse or condone communist influence.

4. Communist influence is pervading the Government and the body politic at an amazingly fast rate.

5. Militant opposition to Castro from without Cuba would only serve his and the communist cause.

6. The only foreseeable means of alienating internal support is through disenchantment and disaffection based on economic dissatisfaction and hardship.

If the above are accepted or cannot be successfully countered, it follows that every possible means should be undertaken promptly to weaken the economic life of Cuba. If such a policy is adopted, it should be the result of a positive decision which would call forth a line of action which, while as adroit and inconspicuous as possible, makes the greatest inroads in denying money and supplies to Cuba, to decrease monetary and real wages, to bring about hunger, desperation and overthrow of government.

In brief, the policy of economic sanctions was explicitly designed to create “hunger” and “desperation,” as a means of undermining and overthrowing a popular government. That policy—which has not changed in more than six decades—was later reiterated in an April 1964 speech to Congress, where U.S. Under Secretary of State George W. Ball put forward the strategy for sanctions against countries like Cuba.

The first goal of economic sanctions is to reduce the will and ability of the present Cuban regime to export subversion and violence; Second, to make plain to the people of Cuba and to elements of the power structure of the regime that the present regime cannot serve their interests; Third, to demonstrate to the peoples of the American Republics that communism has no future in the Western Hemisphere.

On April 23, 1964, the New York Times reported that, in this speech, Under Secretary Ball aimed at “crippling the island's economy” through “a policy of systematic ‘economic denial’ against” Cuba.

The latest tariffs against China are just the latest example of this trend. We know the Trump administration’s anti-communist strategy both because we understand history and because administration officials explicitly admit it. On June 25, 2023, Trump declared: “At the end of the day, either the Communists destroy America, or we destroy the Communists.” He went on to tell his supporters: “This is the final battle. With you at my side . . . we will drive out the globalists, we will cast out the communists.”

The current set of tariffs

On February 1, 2025, Trump first signed an executive order to impose tariffs on imports from Mexico, Canada, and China. Two days later, however, he agreed to a thirty-day pause on the Mexico and Canada tariffs while keeping the China tariffs in place. China rightfully retaliated with its own tariffs on crude oil, agricultural machinery, and large-engine cars imported from the United States.

The following month was filled with further threats and investigations, and on March 4, 2025, certain tariffs on Mexico and Canada went into effect. Trump also doubled his tariffs on Chinese goods, bringing them to 20%. Naturally, all three countries promised retaliation, with China increasing its own tariffs on American farm equipment up to 15%. In the next two days, Trump once again issued a one-month exemption for certain goods for Canada and Mexico.

After another month of threats and retaliatory tariffs, Trump announced on April 2, 2025, his plan for a 10% baseline tax on imports across the board, as well as higher rates for countries that run trade surpluses with the United States. Among other things, he had announced a 34% tax on imports from China, a 20% tax on imports from the European Union, and a 25% tax on imports from South Korea. China, naturally, retaliated with its own 34% tariff on American goods, as well as more export controls on rare earths (materials used in high-tech products like computer chips and electric vehicle batteries).

On April 9, 2025, just hours after these across-the-board global tariffs went into effect, the Trump administration announced that it would be suspending most tariff rates for ninety days for countries other than China. Because he was offended by China’s retaliatory tariffs, Trump announced that he would increase their rates to 125%. China, once again, responded with its own counter-measures, announcing on April 11, 2025, that it would increase its own tariffs to 125%. Importantly, Trump also announced around this time that he would not be imposing tariffs on electronic goods like smartphones and laptops. He apparently didn’t want to be blamed for the sudden spike in prices for those consumer goods.

That takes us up roughly to the present day, but some patterns emerge. Among other things, Trump is clearly more intent on imposing tariffs on China than on other countries. He seems much more intent on threatening those other countries and forcing them into private discussions. This all makes sense, when you view these actions as a direct attack on China’s economy specifically. On April 15, 2025, The Wall Street Journal—in an article titled “U.S. Plans to Use Tariff Negotiations to Isolate China”—explained in detail how “Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent wants trading partners to limit China’s involvement in their economies in exchange for concessions on reciprocal tariffs” (emphasis ours):

The Trump administration plans to use ongoing tariff negotiations to pressure U.S. trading partners to limit their dealings with China, according to people with knowledge of the conversations.

The idea is to extract commitments from U.S. trading partners to isolate China’s economy in exchange for reductions in trade and tariff barriers imposed by the White House. U.S. officials plan to use negotiations with more than 70 nations to ask them to disallow China to ship goods through their countries, prevent Chinese firms from locating in their territories to avoid U.S. tariffs, and not absorb China’s cheap industrial goods into their economies.

. . .

U.S. officials have broached the idea in early talks with some countries, people familiar with the discussions said. Trump himself hinted at the strategy on Tuesday, telling Fox Noticias he would consider making countries choose between the U.S. and China in response to a question about Panama deciding not to renew its role in the Belt and Road Initiative, China’s global infrastructure program for developing nations.

. . .

The tactic is part of a larger strategy being pushed by Bessent to isolate the Chinese economy, which has gained traction among Trump officials recently. Debates over the scope and severity of U.S. tariffs are ongoing, but officials largely appear to agree with Bessent’s China plan.

It involves cutting China off from the U.S. economy with tariffs and potentially even cutting Chinese stocks out of U.S. exchanges. Bessent didn’t rule out the administration trying to delist Chinese stocks in a recent interview with Fox Business.

In brief, the Trump administration is attempting to break the links among countries of the Global South and neutralize China’s economy. It’s not as easy to attack China as it was to attack the small island nation of Cuba, but the motivation is the same: simple anti-communism and economic imperialism.

Beyond simply attacking and isolating China, there are also some secondary imperialist ambitions. On April 7, 2025, Stephen Miran, the chair of the U.S. Council of Economic Advisers, delivered a speech where he expanded on this strategy. After first acknowledging that “the U.S. provides the dollar and Treasury securities” to the world, and that this system has brought “prosperity” (i.e., imperial rent) to the United States, Miran essentially explained the shakedown racket, like a mobster in a movie. He argued that the United States was “under siege by hostile adversaries trying to erode our manufacturing and defense industrial base and disrupt our financial system” (i.e., trying to develop their own productive economies and stop paying imperial rent). With the looming threat of economic protection, Miran explained the shakedown racket:

[W]e will be able to provide neither defense nor reserve assets if our manufacturing capacity is hollowed out. The President has been clear that the United States is committed to remaining the reserve provider, but that the system must be made fairer. We need to rebuild our industries to project the strength needed to protect reserve status, and we need to be able to pay our bills to do so.

What forms can that burden sharing take? There are many options, here are a few ideas:

First, other countries can accept tariffs on their exports to the United States without retaliation, providing revenue to the U.S. Treasury to finance public goods provision. Critically, retaliation will exacerbate rather than improve the distribution of burdens and make it even more difficult for us to finance global public goods.

Second, they can stop unfair and harmful trading practices by opening their markets and buying more from America;

Third, they can boost defense spending and procurement from the U.S., buying more U.S.-made goods, and taking strain off our servicemembers and creating jobs here;

Fourth, they can invest in and install factories in America. They won’t face tariffs if they make their stuff in this country;

Fifth, they could simply write checks to Treasury that help us finance global public goods.

Tariffs deserve some extra attention. Most economists and some investors dismiss tariffs as counterproductive at best and devastatingly harmful at worst. They’re wrong.

Miran is essentially saying that, for the privilege of living under United States global military protection, and for the privilege of getting exploited by United States financial institutions, these countries need to increase their compensation to the United States.

Organizing within the Left

It should already be perfectly clear that the Democratic Party is not a serious ally in the push against the Trump administration’s approach to tariffs. The party that chose to ban TikTok is not a serious party. Rather, we need to defeat the leadership of both parties if we want to really address the underlying issue of imperialism. We also need to build a consensus opposed to these tariffs—not just because they disturb the stock market, but because they are being used as a weapon to bully the rest of the world.

When it comes to material self-interests, it is easy enough to understand that the Trump administration’s tactics may very well backfire with the rising cost of basic consumer goods. It’s also easy enough to understand that other countries have a strong interest in avoiding bullying from the United States. Still, the various European liberal democracies, and weaker nations around the world, might just fold under pressure from the United States. The Trump administration might also selectively ease up on certain tariffs—as it has in the past—to try to avoid the worst spikes in consumer costs. It’s not clear yet how this will play out, and we certainly can’t count on this policy to just collapse in on itself (even though that’s a real possibility).

When it comes to working class organizing, we do need to be mindful of confused messaging and opportunism. Right-wing Teamsters President Sean O’Brien—who spoke at the Republican National Convention last year—has taken the absurd position that Congress should be “putting an end to P[ermanent] N[ormal] T[rade] R[elations] between the U.S. and China,” and has supported the tariff policy (purportedly) on behalf of the working class—or at least those living within the United States. Likewise, at his “liberation day” rally, President Trump paraded around the support of a “UAW Representative” who stated: “We support Donald Trump’s policies on tariffs one hundred percent.” For its part, the United Auto Workers (UAW) has likewise issued statements that “the UAW supports aggressive tariff action to protect American manufacturing jobs.” To his credit, UAW president Shawn Fain has clarified that the Trump administration’s approach to tariffs has been “reckless” and that “we do not support tariffs for political games.” Nevertheless, even though the UAW position has some nuance, this highlights the problems of the current discussions regarding tariffs and manufacturing. Although it’s a good thing to have an industrial policy, and it’s perfectly fine to use tariffs to ensure labor standards, that is not at all what the current tariffs are about. This is not an industrial policy, and these tariffs are not aimed at protecting labor standards. Moreover, what we need is a socialist industrial policy (more in line with the path pursued by China), rather than the protection of inefficient and exploitative capitalist industries. Simply using tariffs to “protect” U.S. industry from Chinese and other competitors is a losing path, for many reasons. It’s further unacceptable that groups like the UAW have put out statements repeating discredited propaganda against China. In short, we need to be vigilant to make sure that working class organizing doesn’t take a simplistic “America [sic] First” turn, and that this type of nationalist chauvinist policy doesn’t take hold.

Socialists must correctly identify what is happening, so that we can appropriately respond. It’s notable that, in an April 12, 2025 speech from the “Fighting Oligarchy” tour, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez assessed the tariffs as a simple matter of market manipulation and insider trading:

We saw this play out this week with Trump’s corrupt and disastrous tariff scheme. I hope that we all see now that the White House’s tariff shuffle here didn't have anything to do with manufacturing, like they claimed. It was about manipulating the markets, it was about hurting retirees and everyday people in the selloff, so Trump could quietly enrich his friends who he nudged to buy the dip before reversing it all in the morning. Donald Trump is a criminal, found guilty of 34 felony counts of fraud, of course he is lying and manipulating the stock market too. He is at his best making himself, the billionaires who back him, and the members of Congress who trade with him rich. Not you, not me, not the people. And to be clear, I don't care what party you are, Democrat or Republican, I don't care what position one holds. Members of Congress and elected officials holding and trading individual stock is wrong, it must end, and we must ban it.

This appears to be a bit of a misdiagnosis of the problem. The imposition of the tariffs has been part of a clear—and very harmful—strategy that is happening out in the open. To his credit, Senator Bernie Sanders has been a bit more direct, stating in response to the tariffs that “we don’t have to hate China,” and should instead “figure out a way to work together.” It’s a very simple and direct message. (To her credit, Rep. Ocasio-Cortez has appropriately voted against some stupid anti-China bills like this and this and this.)

With all that being said, Sen. Sanders and Rep. Ocasio-Cortez have also taken harmful positions on the United States posture to China at various times, with Sen. Sanders repeating slanderous and bogus claims about China, and even voting in 2000 against granting China permanent normal trade relations as part of the country’s entry into the World Trade Organization. When he previously ran for president, Sen. Sanders argued that the United States should “establish a coalition of allies and partners that is agile enough to respond to Beijing's troubling behavior in key areas—including disputes over trade.” For her part, Rep. Ocasio Cortez has worked with Senator Ted Cruz to author a joint letter condemning “the National Basketball Association’s stance regarding its coziness with China versus free speech in America.” These are neither correct analyses nor examples of international solidarity.

What comes next

The Trump administration has been pretty clear that the next step is to drive a wedge between China and its allies. Our task is likewise to drive wedges into the coalitions that the Trump administration is trying to cultivate, as well as to demystify the politics surrounding the tariff process. It certainly appears that the Trump administration has overplayed its hand, and there will be opportunities for socialists to exploit that miscalculation. Even anti-China hawk Gideon Rachman, writing for the Financial Times on April 14, 2025, acknowledged that “Trump has a much weaker hand than he thought in the game of tariff poker that he is playing with China.” Simply put, China makes quality goods and does so at cheaper prices. The trade war will hit consumers, raising the price of some goods and making others unavailable. Looking to the future, Rachman predicts:

Trump hates bad headlines and will want them to go away. So rather than endure the pain of shortages and inflation, he is likely to add more and more items to the list of goods that are exempt from tariffs.

Trump has already done this for certain electronics made in China. Socialists have a political and educational opportunity to clearly convey the link between the trade war and the harm it will cause. However, we also need to be careful not to frame this as just a matter of “free trade” or “cheap goods.” This is also an opportunity to discuss more seriously the deeper issue of how China—a country led by the Chinese Communist Party—has leapfrogged ahead of the United States. It’s worth discussing the response of the Chinese government, and to a certain extent that of the rest of the Global South, to U.S. pressure. Even English-language media has highlighted China’s direct and understandably emboldened position. On April 8, 2025, the Commerce Ministry issued a statement calling the tariffs “completely groundless and is a typical unilateral bullying practice.” In that same statement, the Ministry wrote that the “U.S. should stop using tariffs as a weapon to suppress China economically and stop undermining the legitimate development rights of the Chinese people” and that the government plans to “fight to the end” against this form of U.S. aggression.

The online response has been even better, with English-language news outlets releasing headlines such as China trolls Trump over tariffs as both sides seek ways to limit their impact and featuring an AI-generated meme depicting President Trump, Elon Musk, J.D. Vance, and Marco Rubio working on a production line (see image below). The meme pokes fun at the notion of the U.S. reverting back to a nation focused on manufacturing—communicating effectively in a single image that the loss of U.S. manufacturing power has put it in a weaker material and negotiating position. Anyone in this country could understand why people in China have felt a certain sense of national pride in their government’s response—as reported by Tricontinental journalist Tings Chak at our 21st Century Socialism webinar in early April 2025. In the words of Marxist historian Vijay Prashad, China has articulated very clearly to the United States that it “will not enter another century of humiliation.” There are of course many geopolitical issues that are out of our hands. How China relates to its neighbors under this new tariff regime is an unsettled question. It might be that the United States succeeds in driving wedges between China and the other countries of the world, as it intends to do. Alternatively, if the Chinese Foreign Ministry’s response has been any indication, China might build even stronger ties with its various neighbors in the world, further alienating the United States. If so this moment may present an opportunity to finally end the United States’ imperialist stranglehold over the rest of the world.